Protect yourself: Safety Considerations When Climbing in Spaces with Volunteer Instructors

A volunteer instructor teaching a new climber how to belay from above— directly off their harness with no rope redirect, and with an ATC using the slip, slap, slide belay method. This method of belaying exposes the climber to a high risk of being dropped as the break side of the rope is often not in the breaking plane. Additionally, the belayer in this situation is not braced correctly to hold an unplanned fall. The volunteer instructor is “backing up” the student’s belay but they are also not braced to hold an unplanned fall.

Now, more than ever, we need community. It is important to be able to come together and share positive experiences. To recreate together, to appreciate the natural world, to support one another as we find our growth edge, and to encourage each other to do the best we can.

The sport of climbing has grown rapidly, which is fantastic! Climbing is a wonderful and very accessible activity. Climbing gyms are now found all over the country and with climbing becoming an Olympic sport in 2024, interest in the sport will only grow. With this continued growth, more people are seeking climbing instruction for getting outside of the gym, and many of these people may find themselves in a position where they are being taught by volunteer instructors.

This article aims to provide information for people who climb in spaces run by volunteers so that they can educate themselves on the risk they are exposing themselves to. This is not a definitive list of the risks that can come from rock climbing and I encourage everyone reading this to do their own research on any program they are considering learning from.

I would also like to point out my own bias in writing this article. I work full time as a professional climbing guide and instructor. While acknowledging my bias, I want to point out that I have ten years of experience working and volunteering in volunteer-led climbing spaces, and the bulk of my professional experience has been managing volunteers for climbing nonprofits. I have volunteered 100s of hours of my time to numerous climbing outreach programs in the Pacific Northwest. I have worked for the Mazamas managing their climbing wall and volunteers for youth programming. Additionally, I was responsible for designing and running a successful rock climbing program for a nonprofit called Peak Recovery PNW; where I recruited, trained and interacted with dozens of volunteers.

My intention with this article is to provide readers with information and questions to ask before they blindly expose themselves to risk when working with volunteer instructors teaching rock climbing skills. I want to acknowledge that many climbing volunteer instructors are incredibly skilled, passionate individuals, and I would not be the climber I am today if I had not had access to the affordable instruction that can come from volunteer-led climbing programs.

Traditionally, climbing skills have been passed down to new climbers through mentorship. Mentorship is a big deal in the climbing community and the desire to “give back” has been a recurring theme when people express interest in becoming a volunteer climbing instructor. It is extremely admirable to want to give your time and experience to assist others in finding the joy of climbing. However, I feel it is important to note that not all programs and volunteers are created equally, and the quality of instruction and safety of your environment can vary dramatically with volunteer instructors. We must accept that climbing has become a mainstream hobby with clear and objective risk that we expose ourselves to. Gravity will always win and does not care how well-meaning volunteer climbing instructors are.

Here are some questions to ask when looking at climbing programs with volunteer instructors:

Basic questions to ask about instructors:

Who is teaching you?

What is their experience as a climber, as an instructor?

What is their training?

Who evaluated them and how did that process go?

Organizations will hype their instructors up! That’s normal. But please be aware that “10 years of climbing experience” can mean vastly different things. For some people, that means climbing at the gym 3 times a month for 9 years, followed by a three month outdoor climbing course, and finally taking a gym lead class 10 years in. For other people, “10 years climbing experience” means they’ve led 1000 pitches and climbed multiple Grade IV+ routes. Years doing the sport alone is not enough of a metric to explain how competent of a teacher someone is. Fortunately, there are some questions you can ask to determine how proficient your instructors are before you put your life in their hands.

You can ask how many seasons on rock they have, how many regions they have climbed in, how many pitches they have led, and incidents they have responded to. A good climber to learn from is not someone who has never been in an incident, instead it is someone who is always learning and is able to respond to incidents proficiently. A good question you could ask of a potential instructor is “please tell me about a climb where you learned something meaningful and changed how you thought about climbing.”

You should also ask how many seasons instructing your instructors have, and I would encourage you to dig deeper- ask for how many days in the field they have teaching per year and how many different demographics of guests they have worked with. These numbers are important.

When I was a newer guide working part time, I thought that my 9 years climbing and 500 pitches led were enough for me to be a guide. Looking back, I realize that baseline technical proficiency in recreational climbing was just that- a foundation for my guiding career to grow on. When I worked for a nonprofit, I managed about 25 instructrional days in the field. After moving onto commercial guiding, I racked up 70+ instructional days in the field. I came to realize that I had been making many judgements based on my own confirmation bias- what worked for me and my friends in the past might have only worked for us because we were lucky, strong, and motivated. Once I started guiding full time, my competency as a guide rapidly blossomed. Guiding days and personal climbing days are different metrics to measure and it’s important to know how much time instructional your instructor has.

The thing with personal climbing is that it’s personal. We learn our skills and find processes that work for us and our partners. A person can get lucky 99 times out of 100, and assume that what they are doing is correct because nothing wrong has happened to them, but that mindset takes away your responsibility to yourself and your partner to provide the safest climbing experience possible. In Decision Making for Wilderness Leaders: strategies, traps and teaching methods by Ian McCammon, PhD, McCammon talks about the concept of Heuristic Traps, how we can trick ourselves into complacency. I recommend anyone with an interest in mountain sports read about heuristic traps and reflect critically on the concept.

Some of the big heuristic traps I see with volunteer climbing instructors are Familiarity, Scarcity, and Social Proof.

Familiarity Heuristic “I was taught how to climb by a guy who just took me out and up routes, I’ve taken other new climbers out and up multipitch alpine routes even though they don’t have self-rescue skills, and it has always been OK, so it will be OK today, I won’t fall.”

Example:

In 2023, a volunteer for the program I was running once told a new climber they could clean an anchor while he talked the new climber through the process on the ground-- the person at height had never cleaned an anchor before. The volunteer was an extremely accomplished climber and said he’d taught many people how to clean anchors like this. He said that the climber was in line-of-sight and they could hear each other so it was fine to have them come off belay at height. As the guide managing the entire site, I was not comfortable with this amount of potential risk at my jobsite. I intervened and told the volunteer to lower the new climber so we could teach this skill on the ground. After an anchor-cleaning demo on the ground, the new climber thanked me for telling them to be lowered. The new climber told me they would not have been comfortable with having to clean the anchor at height and did not realize they would have a chance of falling to the ground if things had gone wrong.

Solution: After that outing, I decided to standardize all teaching processes for my volunteer team. I felt it was in my students’ best interest that they were taught skills in a methodical, linear way, and not exposed to the risk of potentially falling from the top of a route while on my watch.

Scarcity Heuristic “Wow, this popular climb is open and my mentee wants to practice cleaning anchors. I’ll put up this cool line because it’s open and they can do their skill practice on it.”

In 2024, a volunteer instructor for a large mountaineering group told me of a situation that occurred when he had a new climber clean an anchor outside. This volunteer instructor told the new climber to thread the rope through the bolts at the top of the route so they could practice rappelling (the route they were on had mussy hooks so the new climber could not pass the rope through any chain rings to rappel) This caused a whole bunch of issues, including the intervention of a local climber who had been climbing the route next door. This local climber was so concerned for the safety of the new climber at the top of the route that they stayed to oversee the rappel. When talking about this incident, the volunteer instructor said to me that he “thought we were just supposed to take the people up cool routes.” He said he didn’t think there was “any sort of standard process for taking the students out.” If I were running that climbing program, I would standardize the outdoor climbing days so that all skills that involve coming off belay, untying from the rope, and removing hardware from the rock we first taught on the ground, then demonstrated at height with direct instructor supervision.

Solution: Standardize skills teaching, seek out terrain appropriate for your student’s goals, and put your ego aside. Climbing skills instruction isn’t about putting people on “cool routes”, it's about giving them the skills to climb on their own. If you want to take people up “cool routes,” go become a guide or some kind of trip leader.

Social Proof: “Sarah you learned to rock climb from volunteer instructors and you’re a guide now, therefore learning from volunteer instructors is fine.”

Example: I was taught how to climb by volunteer climbers and look at me, I’m a guide now, I should be living proof that volunteers are fine teachers, right? Wrong! I became a guide BECAUSE I got so fed up with the erratic quality of volunteer instructors that I decided I needed to change the culture of climbing education.

For example, some of the volunteer instructors I learned from told me that women don’t climb hard, that I needed to be in the “right group” to find people to climb hard with, some volunteer instructors used grossly sexist unprofessional language when talking about climbing technique, and I was told multiple times I would die by following climbing techniques that were not covered in that organization’s basic/intermediate classes. I had volunteer instructors make remarks about how my body looked in a harness that still stick with me today. I was told by volunteer instructors that grigris were heavy wastes of space on their harness and the ATC is superior. Guess what? Grigris are objectively safer than ATCs and the recent trend of gyms disallowing use of tubular devices speaks critically to this point.

Solution: Encourage critical thinking.

————

Explanation of common climbing certifications:

IFMGA, AMGA, PCGI, PCIA and Mountain LEAD are all organizations that certify outdoor climbing instructors, but what do these professional terms mean?

On the surface these organizations all sound the same. They are professional climbing institutions, so they should all produce professional instructors, right? Why am I even typing about professional guiding certifications in an article about volunteer-led climbing spaces anyway?

The answer to that question is because many volunteer-led climbing programs will put their program leaders through some kind of training. Either professionally or some kind of in-house training. And we want this! We want the people who manage the very real objective risks of climbing to be as trained and experienced as possible! However, it is important to understand a little bit about what professional climbing training looks like.

The AMGA is the oldest guiding organization in the US and has the most stringent standards required for taking their courses and maintaining certification. While other professional climbing organizations in North America offer reciprocity for AMGA certifications, the AMGA does not offer reciprocity for PCGI or PICA courses. There are a lot of interesting mountain project forum posts explaining the schism and different approaches to guide training if you would like to educate yourself. My experience with professionals who are certified outside AMGA is that they are willing to offer more flexibility in who they teach, which can be beneficial or problematic depending on the context.

Why does it matter where and how volunteer instructors are trained? It matters, because when an organization boasts that they have “trained guides” or a “trained leadership team,” these phrases imply a certain level of competency and experience. I believe it is important to reflect on what that “training” actually is.

In order to get into an AMGA course, minimum experience requirements must be met. For example, someone who has never placed trad gear would never get into an AMGA SPI course. I have met non-AMGA providers who will waive experience requirements for their courses. As guides we are safety professionals, our job is to manage risk and our ability to manage risk is only as good as our judgment. Personally, I become wary of any program that is lax about their certification and training processes.

———

Questions to ask about the organization:

How is their equipment maintained?

Have there been any significant safety issues? What were the learning outcomes and changes made?

What kind of retention do their programs have?

What kind of continuing education and evaluation process does the organization have for their volunteer instructors?

Does this program have a history of sexual assault, racism, homophobia, or other bigoted behavior?

You can ask to see equipment inspection logs and scope of practice documents. You can ask to speak with the organization’s risk management leader. If the org doesn’t have a person who can speak in that capacity, be cautious! There’s a movement in the industry to have a Petzl Competent Person in every org and it’s a good sign if your organization has a PCP on staff but I don’t consider it a dealbreaker if the org doesn’t have a PCP.

Is there a standard curriculum, method of advancement, and evaluation process for instructors? If so, how is this curriculum designed and how often are volunteers assessed on their technical capabilities?

Why this matters: In 2023 I was taking a course where I was “taught” by a volunteer instructor who said they had signed up to volunteer that night just so they could get a break from their newborn child. Did that person need a break from their baby? Probably, but having a sleep-deprived person who hadn’t climbed outside in months overseeing an exercise where we were practicing multiple rappels (And they couldn’t remember the order of operations for the process they were overseeing us practicing) isn’t the solution. Rappelling is an activity that you don’t want to mess up, errors often result in fatalities. In fact, most climbing skills are activities you don’t want to mess up, you should demand excellence when learning these skills. When you hire a guide to teach you climbing skills, you know that they have a demonstrated level of skill. How do volunteer instructors demonstrate their skill? How and why are you trusting them when it comes to learning?

What kind of continuing safety education exists and is required for instructors? For example, the Mazamas Advanced Rock community does high angle rescue refreshers for volunteer instructors before working on those skills with students. It’s a good sign when the leadership team practices together. If I were managing the Mazamas’ volunteer team, I would have all volunteers demonstrate proficiency in high angle rescue before letting them interact with students in any climbing situation.

In recent years, the Mountain LEAD program has taken off. It’s a way for volunteers to train other volunteers to be better volunteer instructors. I have not gone through this training to compare it to AMGA courses, but my hunch is that it’s a good thing for general climbing overall and a bad thing for guides who primarily work in single pith terrain. It at least recognizes that teaching is a skill just as much as placing pro is a skill, and that making people feel safe and heard in a learning environment will help them learn better.

——

Some climbing programs are known to harbor sex offenders and racists. You can google the climbing clubs in your area and I encourage you to do so before paying to learn from them. The reality is that many large nonprofits struggle with managing the behavior of their hundreds or thousands of members. Most old established clubs have rigid bylaws that are nearly impossible to change, so removing the “bad apples” from the bunch can be very difficult or procedurally impossible, especially if the offending person is a regular volunteer. I encourage you to research the courses you are interested in taking and try to speak to program grads directly. When possible, I encourage you to seek out volunteer instructors who have been vetted and have positive reviews.

____

How long has the organization existed? Established organizations and startups can fill very different niches in the climbing ecosystem. And I will briefly describe the differences between small and large organizations:

Pros and cons of long term orgs.

Pros: they are established in the region, have access to permits and insurance policies that might be hard to get or no longer exist for new programs. Leaders will likely have many years of running programs and managing risk. You can ask numerous program grads about their experiences with the organization to determine if you want to join or not.

Cons: curriculum could be hard to change, might use outdated equipment, tribal knowledge and cliques can form, often there is an “old guard” in key leadership positions who may be resistant to change. Might have to work against their reputation in the community. Large organizations might care more about their financial situations than individual participant experiences.

Pros and cons of startups.

Pros: can exist to serve an unmet need, can bring in new ideas and serve unserved populations. Can write volunteer policies that are stringent with behavioral expectations and kick out “bad apples” from the group.

Cons: could be run by inexperienced people, might lack back-end policies that ensure smooth operations, might be so eager to serve that risk isn’t properly managed, do they have proper insurance and experienced instructors?

——-

My personal opinion is that you should not sign up for a volunteer-run climbing program if the program director does not lead climb outside, have at least 50 multipitch climbs that they have led, have at least an AMGA SPI certification, and ideally at least a season of professional guiding instruction in the private sector. I believe people without significant outdoor leading experience do not understand the nuances of outdoor climbing risk management. People who do not lead and outsource that risk to guides or mentors have not developed enough as climbers to run a climbing program.

The good news is that there are volunteer-led climbing programs that meet these criteria. There are also many, MANY guiding services that will also teach you climbing skills- often in a way that has better managed risk and client learning outcomes.

Organizational leadership and safety standards start at the top and work their way into every facet of a climbing program. It is important that the people who run the volunteer climbing program understand the risk they are managing because it literally is your life on the line in this sport. You should seek out the most experienced instructors with the highest level of professional certification you can find.

Make informed decisions and use your best judgment. If you have questions about how your volunteer instructors are teaching and managing risk, please speak up! Take a minute to look beyond a pretty social media presence and all the smiling summit selfies, dig deeper and verify the people teaching you critical safety skills have the experience and discernment to manage risk as safely as possible and have fun!

I hope this article has been informative and helpful for anyone looking to learn from volunteer-run climbing programs. Climb on ✌🏻

Moving On: Healing From Healing After Five Years Sober

Skiing down Mt St Helens in 2021 and looking towards the horizon.

Five years ago I decided to stop drinking alcohol. I never imagined where I would be today.

In the past five years, led my first 5.10, led my first 5.11+, climbed a my first Grade IV and V routes, led over 650 pitches of rock, climbed 1000s of feet of alpine rock, became a single pitch instructor, designed and led a successful recovery climbing program, led my first ice climb, became an instructor for the Mazamas, developed a serious yoga practice, was promoted to Program Coordinator at my dream job, got into the AMGA all women’s affinity Rock Guide Course, and found the love of my life.

I also weathered the pandemic and the loss of my art business, lost part of my vision when my retina detached and had to come to terms with permanently altered depth perception, went through focused therapy for PTSD associated with breaking my leg in 2018, spent four months battling chronic fatigue from iron deficiency anemia, became a recovery mentor and held a lot of space for some seriously hurting people, unexpectedly lost my dream job, experienced a traumatic climbing accident, found a new job working long hours commercially guiding, and made the hard decision to postpone my rock guide course because I was hearing the call of the void while leading.

It’s been a lot. I am tired.

I’m tired of healing, I’m tired of trauma, I’m tired of “being in recovery.”

And you know what? I can move on. I can decide for myself that I no longer identify as ‘in recovery,’ I can just be Sarah. I can recognize that at points in my life, I have experienced pain or unfairness, and I can let it go. I do not need to be defined by, or hold onto my self-limiting beliefs that were born from a place of mental scarcity.

There have been times that I needed help and I sought it. There have also been times I set goals and achieved them. I am ready to move in the direction of achieving more goals.

To be truthful, after my first year of sobriety, I did not experience cravings for alcohol. Once I removed the unhelpful influences from my life, it was easy to fill my cup with joy. It was not until I began working in the recovery field that I felt tested again. My last job required a lot from me. It required me to state publicly that I was ‘in recovery,’ and it boasted that ‘recovery is a lifestyle.’ While I am honored to have been able to facilitate positive climbing experiences that allowed people in recovery to build self esteem and make better choices for themselves, I no longer wish to define myself by the past.

Growth requires that we let things go. We can’t expand into our higher selves without letting go of the things and beliefs that no longer serve us. At this point, I do not believe I am in recovery, I believe I am Sarah, just chilling and living my life. My intention is to look forward to the rest of my life and live with peace and joy.

Psychological considerations for guides working in affinity recreation spaces

Affinity group definition: An affinity space is a safe place for a common identity or social group.

I have been involved with affinity climbing spaces since 2014: women's climbing groups, young people's adventure groups, queer and LGBTQ+ climbing groups, youth outreach and therapy groups, and recovery climbing spaces. In fact, I learned to climb within the safe space of an all women’s affinity group. In the last decade, I have been involved in these spaces as a professional leader, volunteer, and participant. Over many years working in the field, my relationship with climbing has become enmeshed with my identity as a person. It is often difficult to discern where I end and Climbing begins.

When I suddenly lost my dream job as Program Coordinator for an affinity program earlier this year, I was shaken to my core. I felt like I lost sight of who I was as a person and questioned if climbing even belonged in my life anymore. The experience encouraged me to deeply reflect on what climbing meant to me as a person, instead of just an affinity group member.

It is noble to wish to serve others and share adventure sports with underserved populations. These activities can be the source of great positive transformation, but there is much I wished I had known before going into this field. In light of my recent professional heartbreak, I have decided to postpone my Rock Guide Course until I can recalibrate my relationship with climbing and guiding so that is on my own terms.

Please note, these observations are only my singular perspective, and are based on my lived experiences.

Having a shared background can activate your past experiences. How prepared are you to be triggered at work? What type of boundaries do you exercise between yourself and your guests? What is your support system like for when you are inevitably triggered at work? Are you compensated for the time you spend recovering from being triggered at work? Does your program leadership recognize the massive emotional load that this work can carry?

People who self-select to participate in affinity spaces most likely will have a certain level of discomfort in the general population. There is a reason they chose to opt out of the mainstream population. As a guide, how trained and prepared are you to manage that discomfort? Some examples of discomfort I have witnessed are volunteers telling me they are not comfortable riding in cars with men, participants being uncomfortable around other participants due to their substance use, participants telling me about truly horrible events they have experienced, and volunteers telling me they have been kicked out of “mainstream” groups due to personality reasons.

Having a shared background means you will feel more connected to your guests. Are you okay with that? You can’t fix people by exposing them to adventure sports, they have to decide to fix themselves. You may also find that you are more attached to these guests than to guests with whom you do not have a shared background with. Are you okay with that and are you aware how that attachment can affect your judgment? Guides talk about “firing clients” but how will you feel when you inevitably have to “fire” a very emotional member of your affinity group? In my own experience, “firing clients” in a peer support affinity space felt incredibly taxing, and I doubted myself about my decision. Looking back, it is a decision I wish I had done sooner, but because I was emotionally connected with these people, I gave them more chances than they deserved.

Important question: How do you reconcile creating community with managing risk in an outdoor environment where your professional reputation is on the line?

Boundaries get weird in affinity spaces. In my last position, over 50 people had access to my personal email and phone number. It was not until I had been with the program for a year that I was given my own cell phone to use for work. This created a substantial invasion of my personal life and privacy. Imagine walking to yoga and receiving text messages on your direct line from past students begging for help with an unsafe climbing scenario, what a serious invasion of your peace! If your affinity program does not provide staff with resources and training to draw appropriate work/life boundaries, that is something you must advocate for.

Do you also manage volunteers in an affinity space? Volunteers will likely have similar experiences that are common within your affinity group. Ethical volunteer management is quite tricky and I am writing more on this nuanced subject in a coming article. Understand that volunteers who self-select to work in affinity spaces have their own motivations that will likely feel very strong. In these situations, emotional buy-in can be very strong and perhaps overdeveloped. Your job as the guide managing this team is to keep everyone safe while discouraging cult-like mentalities from developing.

Above all, you must champion the best safety practices of your industry. Workplace safety is more important than fostering community.

In addition to your guests, volunteers, and yourself; your employers and board members are also likely part of the same affinity group and will likely bring strong emotional connection to the work you do. While a strong emotional connection to the cause can be inspiring, unchecked emotional connection to the work can create volatile and enmeshed work environments. You may find yourself having to navigate supervisors with strong emotional connections to your affinity group. It is possible that being so emotionally connected to the cause can blunt people’s judgment. Organization leadership can become so mission-focused that they forget to consider the people involved, including you. Your organization should exist to serve the population it is created for, not the egos of leadership.

Affinity spaces are often nonprofits and thus operate at the whim of grant providers. Your job will never be secure. You may find yourself performing tasks that are not in line with your vision because your organization needs the grant money. You may disagree with how leadership and board members go about securing grant funding. Are you okay with your work sites and guests being documented and posted on social media? Are you okay with having to structure your site days so they become elaborate photo shoots? How will you decide between honoring your guests’ privacy and the fact your organization needs cool looking footage for their social media accounts?

On the subject of social media, are you okay with your own personal life and story being shared on social media? As a guide and leader in an affinity space, you exist as a product to be sold to potential guests and donors. Your image and story will be used for marketing. In my experience this can feel extremely invasive and can also be distracting from the work you are doing. Of course, there is also the element of selling yourself in commercial guiding enterprises, but most often those outfitters will want to boast about your technical skills, experience, and positive attitude rather than lived microaggressions and past trauma. After being active in affinity climbing spaces for a decade, I am finding it quite freeing to “opt outside” of the affinity space for a bit. It’s totally okay to ‘just’ be a guide or ‘just’ be a climber.

At the end of the day, my advice is this: don’t give yourself away for free. Demand competitive wages and benefits. You do not need to be reachable 24/7/365. You do not need to do all of your recreating in affinity spaces. It is okay to take breaks from affinity spaces. It is okay to have professional boundaries. It is okay to just climb for yourself. In fact, I encourage it.

Rock Climbing as a Transformational Activity for People in Recovery, a Reflection on my time with Peak Recovery PNW

The June cohort celebrating on top of French’s Dome

I am so proud of the work we did with Peak Recovery PNW and am deeply hopeful that everyone involved in this project can look back on it fondly. While it’s unfortunate what happened with the program not being able to continue as it had previously been, I believe that the lasting lessons of Peak will live on. I for one, am extremely grateful for the time I spent working with Ali, Brent, and everyone at the Alano Club as well as our partners at the Mazamas. We did something no one had really done before, and all of my future guiding work will build upon those lessons.

In 2022, I was offered a job as the Lead Climbing Instructor for a new nonprofit and jumped at the opportunity. Brent and Ali put a tremendous amount of trust in me to build out my own climbing program for Peak. Over the following months, I spent a lot of time reflecting on what I wanted my program to look like and how could I build a space that was welcoming enough and safe enough so that people could come together to learn new skills while building recovery capital. Recovery capital is an industry term referring to the internal and external resources necessary to achieve and maintain recovery. Basically, it’s all about finding ways to live a fulfilling life that doesn’t involve substance.

A student reaching the top of French’s Dome

Thinking about my own experiences with recovery and reflecting on how climbing has been historically taught in guided and volunteer-run courses, I knew that the rock climbing program I would design would need to look and feel different from the established “learn to climb” classes. I did not want to overload my students with too many knots and skills to practice, I wanted them to build confidence in themselves over time. The primary goal of Peak Recovery was to build recovery capital, so I structured my classes and outings around building community and creating connection points between participants. To me, it felt better to teach fewer skills better, than to teach lots of skills without adequate time for those skills to crystallize. For these reasons, I chose to create a list of core skills for the class and make sure students had many opportunities over several weeks to practice them.

Many people, myself included at times, have a perception that climbers are all thin and fit beautiful people with lots of muscles. That perception of what a climber looks like can be harmful and deter people away from the sport. The truth is, anyone can climb. It was important to me to keep this class as approachable as possible for all skill and ability levels. I chose crags with short approaches and did my best to make sure the routes were accessible and fun to all ability levels. People have different learning styles and I wanted to make sure that students could build their skills in a controlled way. At the end of the day, most beginning climbers are probably going to stick to climbing at the gym or simple outdoor cragging for the first few months after they learn to climb. I chose to design a course that would set them up to confidently pass a gym belay test and top rope in single pitch terrain.

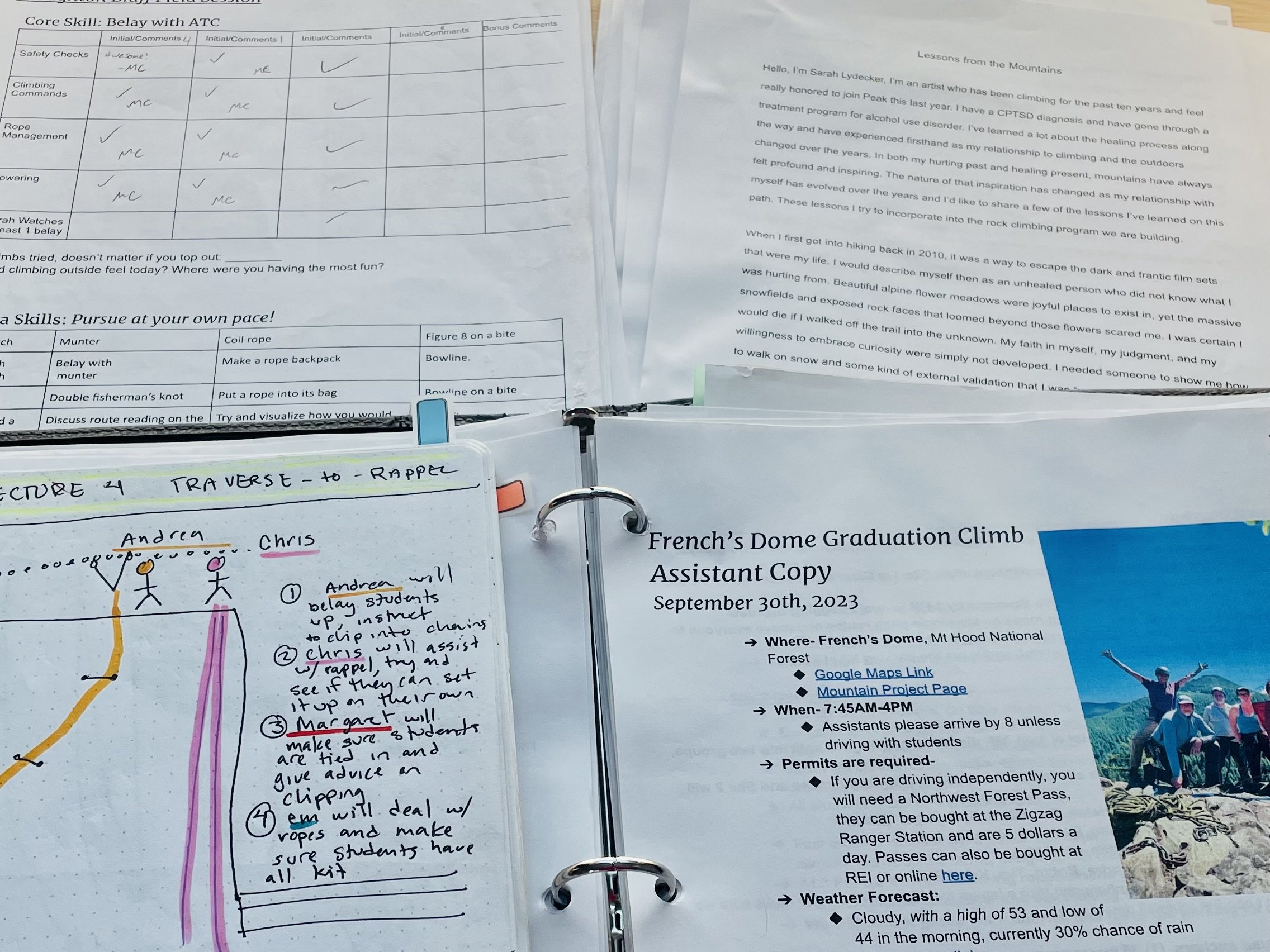

The core skills taught in the Introduction to Rock Climbing course

In addition to educating my students, I was responsible for sourcing, vetting, and training volunteers. I have had experience doing this when I worked for the Mazamas, but it is harder to recruit volunteers when you are a new organization. I took time to connect with each volunteer, determine what kind of experience they had and what they were hoping to gain by volunteering. Recruiting volunteers is a challenge for many reasons, and their wellbeing was a concern of mine. It’s no fun to volunteer somewhere and get all the bad jobs or not feel appreciated. Making volunteers feel appreciated was an important step in building recovery community and building a sustainable program. I was so proud that 5 of the 6 graduates of my June Intro to Rock Climbing course returned to volunteer in the September course. That’s a small sample size, but also a really promising one!

Each course had 4 climbing skills lectures at the Mazamas Mountaineering Center and 4 outdoor climbing days. We visited different crags and students were exposed to a wide variety of climbing.

As a guide, I needed to determine the best practices for how safety decisions were made, what equipment was used and how it was maintained, and manage group safety at sites that had up to 26 people. I researched and wrote up documents for best safety practices, inspected gear and maintained rope use logs, and made decisions about which volunteers and assistants to promote in terms of skills they could teach. For each classroom lecture and outdoor climb day, I made two sets of documents, a student set and an assistant set. My goal was to be as clear as possible about who was doing what and when it was happening. For our outdoor climb days, students focused on learning the core skills of the course, if they wanted additional challenges or learning opportunities, I created a menu of skills they could work on. Things like learn to read a climbing guidebook, coil a rope, or tie a bowline knot.

Some of my instruction materials

My intention with volunteer management was never to create a culture where people felt they had to commit to more than they were comfortable with. I wanted returning program grads to always feel it was okay to join one of our climb days and help out or be present at the level that felt right for them. We all have a lot going on in our lives, and I didn’t want any of my program grads to associate climbing with obligation. I let them know I would never hold it against them if they didn’t show up in a volunteer capacity. Managing assistant volunteers was a bit more challenging, because you simply need a certain number of people to mange climbing sites. If no one who shows up can lead belay for example, then we would need to go to sites with top access and change plans.

In November, Peak presented at the Mazamas Holman Auditorium and I was honored to share a bit of my story and hear from program grads and volunteers how much this program has helped them out. I don’t often talk about my recovery journey, it’s a private matter and I prefer to talk about climbing instead. Being in a room surrounded by dozens of supportive people was really special and seeing how many of my students came out to support the program was really special.

Speaking at the Peak Recovery presentation in November 2023

I am deeply sad that my time at Peak Recovery PNW is over, but I am so proud that the work we did contributed to people making better choices for themselves. Through climbing, we can attain heights previously thought impossible. These heights can be physical when we do big climbs, but they also be personal- the accomplishment of feeling relaxed in a group of people, laughing while belaying a friend, or coming to terms with a fear of heights. Our personal wins don’t have to be big fancy gestures. One of the biggest wins I experienced as an instructor was when a student took a nap in the Peak van, this person felt safe enough around us to take a much-needed judgement-free nap!!!

Moving forward, I hope to work with recovery groups in the future. I think people have this idea of what a climber is and think they can’t possibly be a climber because they don’t fit a certain mold. But the truth is, everyone can try this sport out if they want, and it really does not matter how good you are at it, what matters is that you are having fun.

The group getting ready for a full day of climbing at Horsethief Butte

Thank you so much to the dozens of people, sponsors, and organizations that came together to make Peak Recovery possible.